When I almost lost access to my Gmail account.

With scams and fraud on the rise, I thought I’d share a personal “near miss” experience and the steps I took to minimise the risk of it happening again. Hopefully this will never happen to you or anyone you know, but if it does, it may be helpful to know what to do and how to spot the warning signs.

Wednesday, 9th October 2019

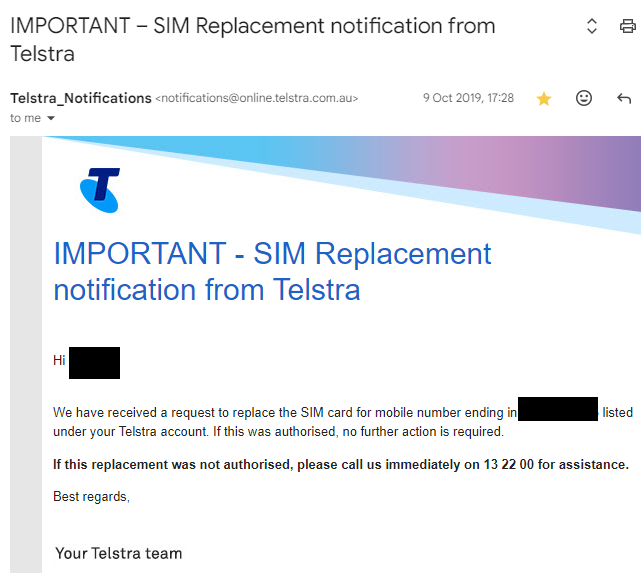

I was working from home and just as the last meeting wrapped up at around 5:30 PM, I noticed my phone signal drop out and a Telstra email notification appear.

Initially I didn’t pay too much attention to the email and thought maybe it was related to why I had lost phone service.

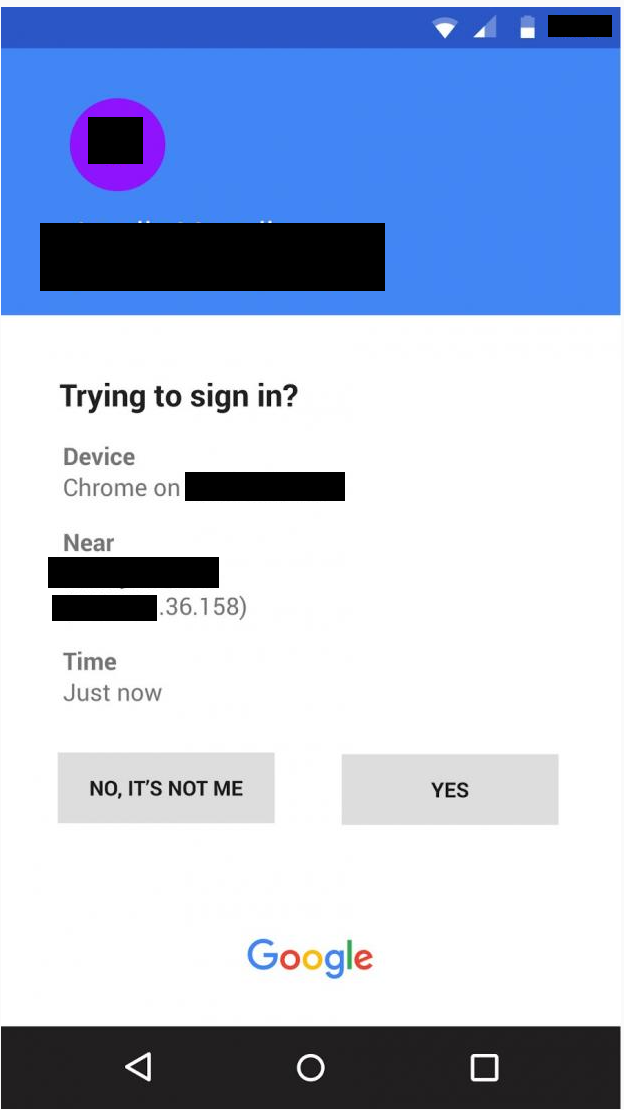

Moments later I received another notification on my phone that someone was attempting to sign into my Gmail account, asking whether it was me.

I quickly clicked NO, IT’S NOT ME as my heart started to race in a moment of panic and confusion. For the next minute, I had several of these prompts appear, to which I had to repeatedly click NO while fearing that I was about to lose access to my Gmail account.

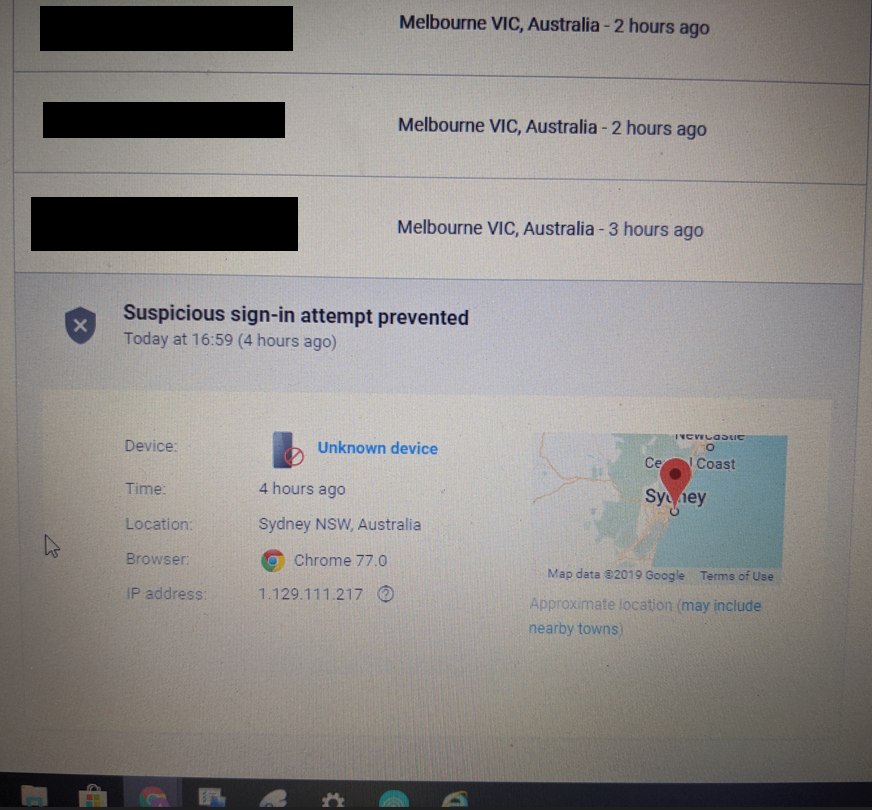

The prompts eventually stopped, and as I began to gather my nerves, I recalled reading an article about the warning signs of losing access to your phone network and what it could potentially mean.

I then realised I was a victim of a SIM-swap attack, and the attacker was attempting to take over my Gmail account.

A background on unauthorised SIM-swapping: An unauthorised SIM-swap attack occurs when an attacker convinces a telco customer service representative (over the phone or in person) that they are you, so that they can move your phone service from one physical SIM card (the one in your phone) to another physical SIM.

The attacker likely has their new, blank SIM card physically in their hands so that they can read out the SIM identifier to telco customer service over the phone.

After the SIM swap (porting my number to the attacker’s new SIM) is complete, which can take place in a matter of minutes, the attacker can then use my phone number with complete freedom to send or receive SMS and phone calls. Then my SIM card in my phone will be rendered inactive.

While the attacker was not successful at gaining access to my Gmail account, had I been at work or on the way home from work (likely the attacker’s intention behind the 5:30 PM timing), I wouldn’t have had WiFi and therefore wouldn’t have been able to receive and decline the sign-in prompt. This could have resulted in a much worse outcome, with the attacker gaining access to my Gmail account.

After the Gmail sign-in attempts stopped, I called my wife (using Whatsapp over WiFi!) to ask if she could quickly come home so that I could use her phone to call Telstra and seek help on how to manage the situation. After navigating through first-line customer service, I was eventually able to speak to someone from their fraud department.

During this stressful experience, it was relieving to be assigned a dedicated Telstra fraud specialist with a direct contact number, who was able to talk me through what had happened and the next steps.

Thursday Morning, 10th October 2019

Based on the advice of the fraud specialist, I went to a Telstra store to verify my identity in person and port the number back to a new SIM card.

Reflection: I was without phone service for the entire time between the unauthorised SIM-swap and when I went into the Telstra store (~15 hours). This meant that, depending on other information the attacker had on me, they may have called banks using my phone number and impersonated me.

At the time, I didn’t think to call my banks to ask them to freeze my accounts. I also didn’t think to call my phone number from another phone (ideally with caller ID disabled to limit any additional information given to the attacker) to understand whether the attacker had successfully ported the number or whether it was locked by Telstra.

While the Telstra store staff were finalising the new SIM for me and writing notes in their system, I could see their screen and where exactly on the customer relationship console (it looked like Siebel) they were capturing the notes.

I asked if the console had something to indicate that the account had been compromised. They scrolled to the bottom of the page, as if it were the last place someone would look, opened the notes from the night before, and we eventually found some brief notes about the fraud incident! This is in strong contrast to how fraud is managed in banking.

I am vaguely familiar with the banking process, which involves applying a fraud flag to the account so that the next time the customer profile is pulled up for an enquiry, bankers will treat the account with an elevated level of caution.

In some earlier notes regarding the actual fraud incident, I also read…

“…activated the blank SIM card for his mob xxxxx. Phone was lost…unlisted; caller ID off.”

In other words, the attacker was able to use social engineering (claiming the phone was lost) to bypass the security measure whereby telcos must send an SMS with a code, which is then read back to them to verify that you are in possession of your own SIM card.

This was over five years ago, so I would hope that by now Telstra have enhanced the functionality of the console to make it more obvious that any account maintenance on compromised accounts requires an elevated level of caution.

SMS two-factor authentication (2FA) vs. SMS account recovery

You’ll probably most often hear about SMS two-factor authentication, where, in addition to a password, the SMS acts as the second layer of protection. In my view, this is an effective way to employ SMS to enhance account security. For example, when you want to add a new payee to your banking account, you will likely receive an SMS as a second factor authentication (the first factor being logged into banking with your password).

The other way SMS is used, which is not so much a security enhancement, is for account recovery. Account recovery is required if, for example, you forget your Gmail password and need to reset it. In this case, the SMS is acting as the one and only authentication to access Gmail and was the precise feature that the attacker was exploiting while attempting to take over my Gmail account.

At the time, it wasn’t immediately obvious to me that this is how I had set up my Gmail security settings. From a security perspective, it makes no sense to have SMS enabled for both 2FA and account recovery, since the 2FA can be bypassed by simply resetting the password (via account recovery).

Reflection: As mentioned earlier, I was without my phone service while being asleep. This meant that the attacker may have attempted to phone-recover my Gmail account while I wasn’t awake to decline the sign-in attempt. Fortunately, for whatever reason, this did not happen.

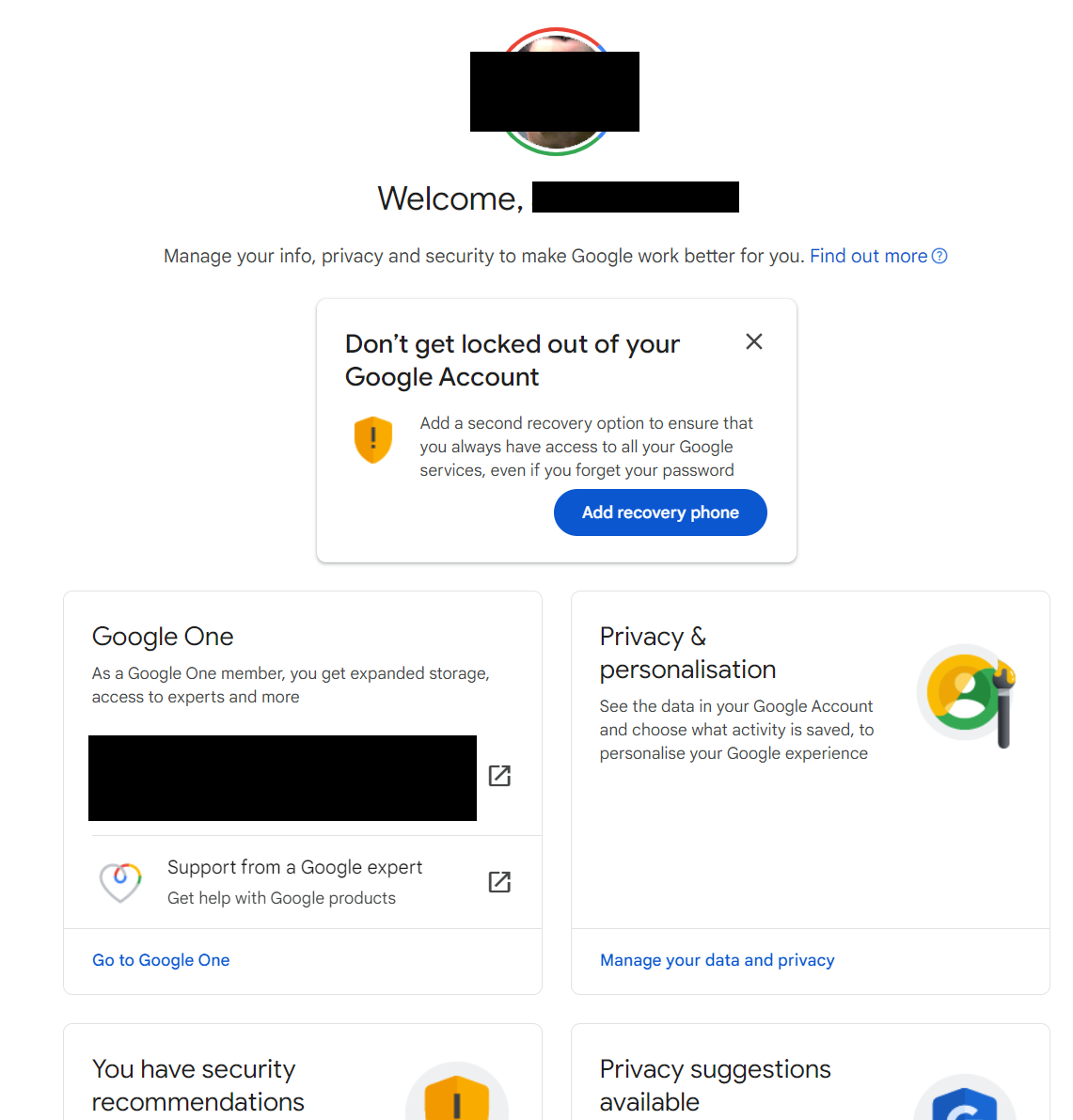

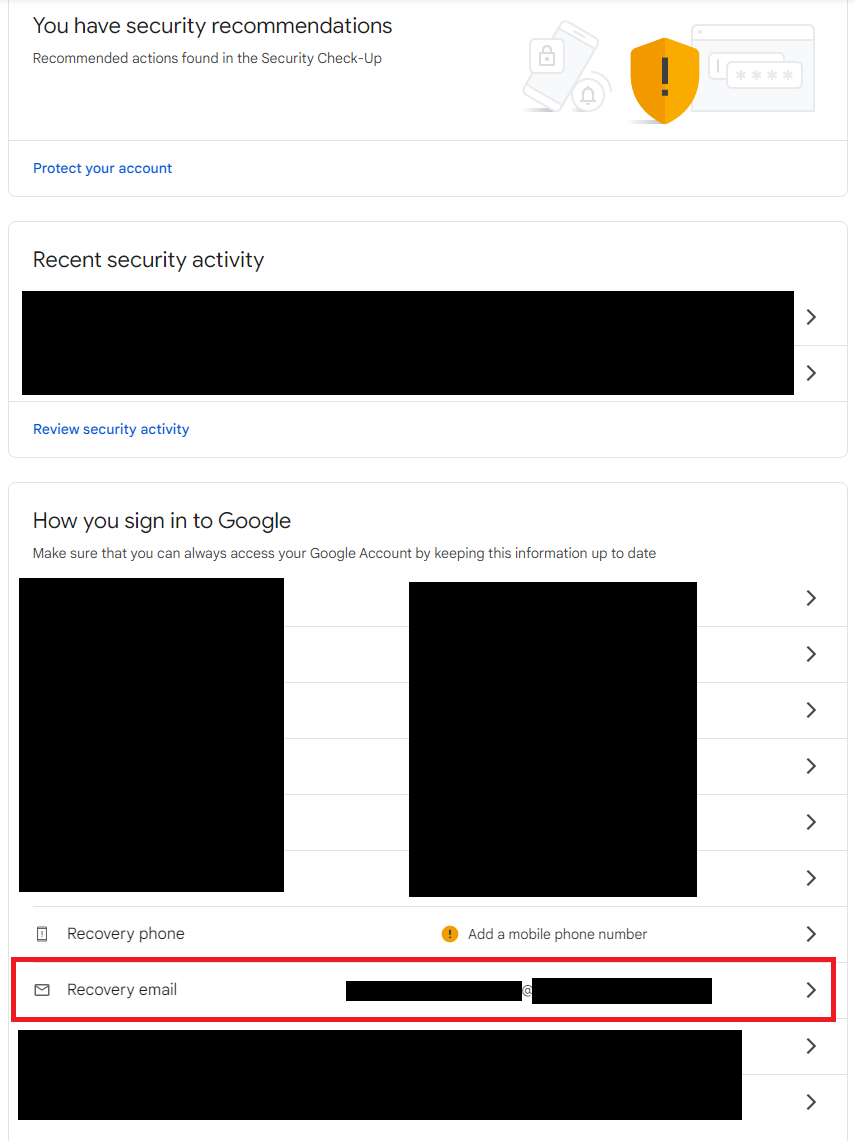

Currently in the main menu of Google’s settings, they make it very obvious that I haven’t added a recovery phone. Given that I have a recovery email set up, I’m not sure whether their intention is to ensure that I’m not locked out of my account or to enrich their datasets for more targeted ads.

For now, I have decided to not have phone as a recovery method and rely on another email that I know I’ll always have access to. Depending on your circumstances, this might be a good configuration for you.

Thursday Evening, 10th October 2019

It was around 5:30 PM when I received an SMS from Telstra. It contained the SMS code that was to be used as part of setting up a new SIM card!

It’s likely that the attacker was making another attempt to swap the SIM and perhaps wasn’t as successful in convincing the Telstra service rep to process the swap without having access to the device and the SMS code needed to complete the SIM swap.

In my opinion, if Telstra had a more effective console feature or process to clearly indicate that the account had been recently compromised by fraud, the attacker would have been denied access within the first seconds of the call. This would have prevented the attacker from progressing through the SIM swap process to the point where a SIM swap SMS was triggered.

Friday, 11th October 2019

Based on the advice of the Telstra fraud specialist and acknowledging Telstra’s lack of controls to manage my attacker’s persistence, we agreed it would be best for me to create a new account with a new number under a different name (someone close to me). Of course, this meant I would need to contact my bank and update the phone number everywhere it was used, but I felt the risk was too high to continue with the same number.

My theory on how the attacker was able to successfully ID themselves with Telstra

Recalling that the Telstra fraud specialist mentioned the attacker knew my account number, it became clear that this was a key piece of information used to convince the Telstra representative that the attacker was me. Since my bills were sent via email, the only other possible way for the attacker to obtain the account number would have been through the Telstra online customer portal.

A background on credential stuffing: Sometimes we need to create usernames and passwords for relatively benign websites, like 247backgammon or Wordle Online. These websites often have less than ideal security measures in place, making them more susceptible to hacks. As a result, their lists of users’ emails and passwords are more likely to be hacked and sold on the Dark Web.

For some unfortunate Wordle Online users, their email and password may have been the same as those used for more sensitive websites like Telstra’s online portal. This becomes an issue when savvy hackers purchase the Wordle Online dump and decide to test it against the Telstra login portal, attempting to log in with each credential one at a time using custom software. Hence the name ‘credential stuffing’.

I think that some of my credentials were stuffed into the Telstra portal, allowing the attacker to successfully log in and determine my phone account number and birthdate stored in the Telstra system. This information was then used to convince the Telstra service staff that the attacker was me.

An extra tip on minimising the impact of data breaches: Often, websites will ask for your full name, birthdate, and other personal information that isn’t always necessary for transacting with the service. This increases your potential exposure to personal information leaks online.

For example, I have a Coles Online account that requires a valid birthdate. Does Coles really need to know my exact birthdate? I’ve made many Click and Collect orders, and whenever they’ve requested to see my driver’s license, they’ve never bothered to check if the name and birthdate match.

If there is no use-case for having your birthdate, then err on the side of caution and provide one that is perhaps a different day and month. That way, if Coles Online is ever hacked and leaked onto the Dark Web, the incorrect information will make it difficult for any fraudulent activity.

The cleanup and moving forward

As I wasn’t sure what other information the attacker had about me, I subscribed to Equifax’s credit and identity monitoring services to monitor whether the attacker was also applying for credit using my identity. I continued this for around six months on a monthly subscription until I was comfortable that the dust had settled and the attacker had moved on.

Phone numbers are quarantined for six months (possibly longer for those involved in fraud). After a number comes out of quarantine, it may be used by someone else, so it’s important to ensure that all of your banking, emails, MyGov, and anything else attached to the number is updated as soon as possible.

I created a long list of everything linked to my old phone number and slowly worked through it. Be prepared to show some additional form of identification to do this, as the process typically relies on an SMS verification message to the existing phone number.

I also had another, longer list of all my online accounts which required their passwords updated and I used that opportunity to move to a different password manager 1Password. While I could have used Google Password Manager, it was integrated with the Gmail account that was almost taken over, so I didn’t think that was a wise security decision.

I’ve read a few stories of people randomly getting locked out of their email accounts due to glitch-induced lockouts (unrelated to fraudulent activity). For those who are lucky enough to get enough attention on Twitter, Google reviews their accounts and makes special arrangements to unlock their access. Commentary on these events always highlights the saying, “if you’re not paying for it, you’re not the customer.” That’s why I chose Fastmail, a paid email service headquartered in Melbourne, which gives me peace of mind knowing that I have better support and security.

Another tip on minimising the impact of data breaches: Fastmail has introduced a ‘Masked email’ feature that allows you to generate a random email address (at the Fastmail domain) which will receive emails into your main Fastmail inbox.

This means that for each online account you create, you can have a unique email, making it very difficult for user credentials to be stuffed into other platforms.

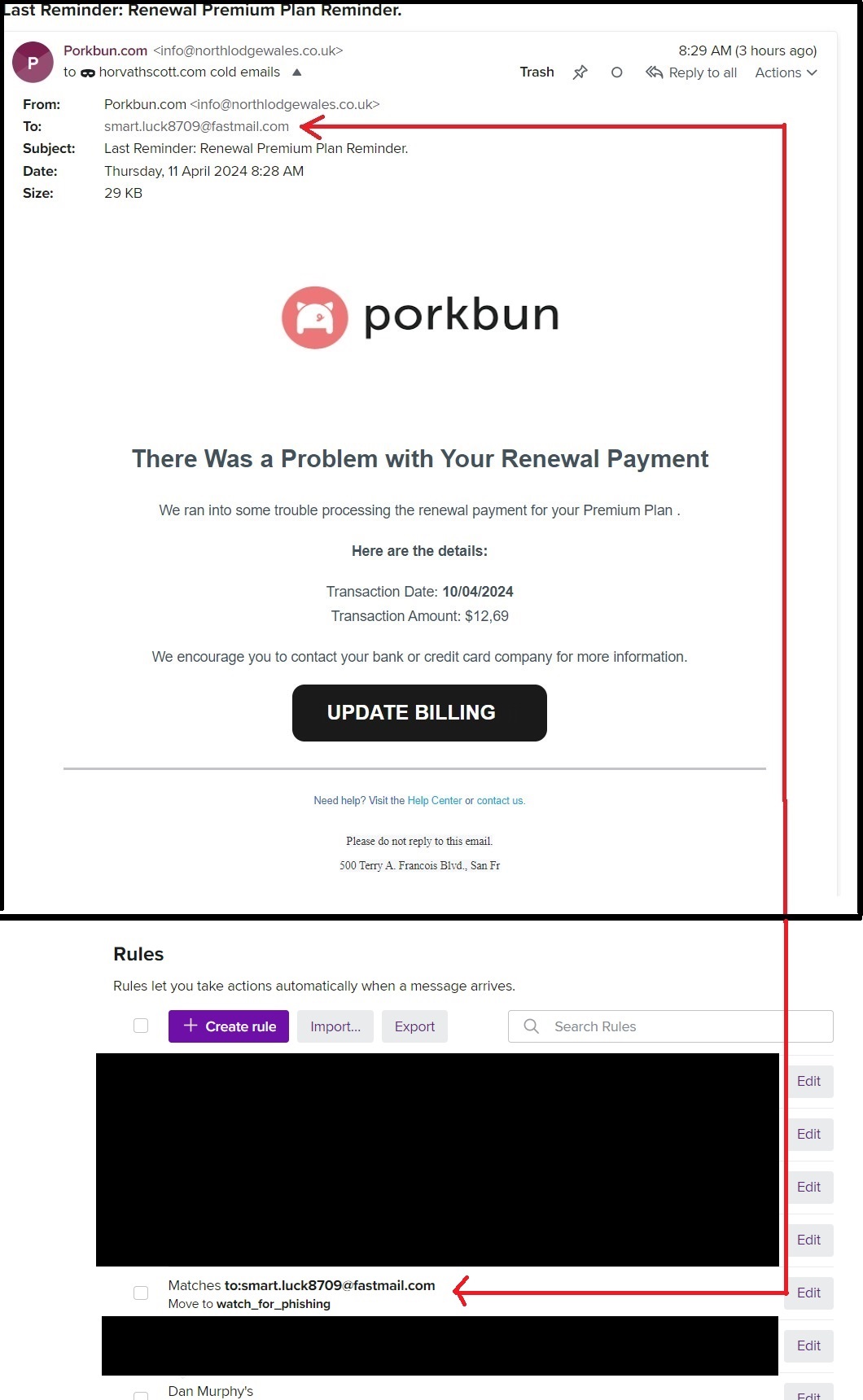

For example, this email address smart.luck8709@fastmail.com is one of my many masked emails that I have generated, which I have reserved for the purpose of a ‘contact me’ section on my blog.

Fastmail is also the only email provider to integrate masked emails with 1Password. When you sign up and create a login for a new website, the 1Password Chrome extension will automatically ask you whether to create a masked email. This triggers Fastmail to create the masked email and populate it into 1Password.

Another benefit of using masked emails is that you can anticipate the types of emails you should expect to receive at each address.

For example, someone was able to detect where my blog domain name was registered (Pork Bun) and craft a phishing email to elicit my credit card details. This email was so convincing that I clicked on it and started to enter my card details until I realised the web form URL wasn’t Pork Bun. Since then, I have added an email filter within Fastmail so that any emails sent to this address are automatically added to a folder called “watch_for_phishing,” prompting me to be suspicious of them.

Acknowledgement

Throughout the first few weeks of this very stressful experience, I was fortunate to have a friend who helped calm my nerves and quickly formulate a strategy to manage the incident. I would like to extend my heartfelt thanks to Ash Sharma for his invaluable support and assistance during this time.